“Economics unfolds in shades unseen. Shadow pricing, a beacon in the fiscal dusk, illuminates the value of the immeasurable, forging a path to enlightened choices.”

We face uncertainties every day, with every decision we make. The gravity of the situation multi-folds when the decisions become economic and financial. Shadow Pricing is one such concept that alleviates the fogs of uncertainty from the decision-makers’ desks.

Businesses and economic entities use shadow pricing to assign monetary values based on assumptions to their abstract commodities, such as externalities and intangibles. These commodities are not only difficult to quantify to set a market price, but also come with their caveats changing the balances of cost-benefit analyses.

A cost-benefit analysis is a systematic and detailed process that businesses adopt to weigh and analyse the decisions they must take and forgo. This analysis is the difference between the expected rewards from a situation, decision or action and the total costs incurred to implement it.

Shadow pricing enters the situation as it is beneficial for tackling the challenges in economic decision-making when valuing intangible or non-market factors. Various factors act interconnectedly, which makes the process complex with a plethora of limitations. Factors like subjectivity in judgments, heterogeneity in preferences, and perceptions across cultures and individuals alter the values of intangible assets. It makes it challenging to achieve a universally accepted value for intangibles.

Intangible assets do not have readily observable market prices. It’s almost a very complex task to isolate each of their ways and analyse their contributing factors independently. It impacts the investment decisions and the overall decision-making efficiency of an organisation. Moreover, intangible products and services, like innovation, brand perception and reputation, can evolve drastically. Predicting and quantifying their future prices is unpredictable and unreliable here. Accurately evaluating their present value becomes a challenge.

This article aims to provide a comprehensive view of shadow pricing and its economic impacts and essentiality in modern business practices.

The Concept of Shadow Pricing

Shadow prices indicate the intrinsic or real value of a factor or product relating to equilibrium prices. These prices may deviate from market prices depending on the nature and size of market distortions like non-competitive behaviour, externalities, etc. Shadow prices are also accounting prices as they are used for accounting purposes in contrast to market prices.

Generally, the concept of shadow prices is used to estimate the price of an abstract commodity that is not bought and sold in the market, unlike tangible and intangible goods and assets. This assignment of price is attributable to conducting a cost-benefit analysis. Such an exercise is particularly useful in the case of evaluating various public policy and infrastructure proposals such as tax rebates, subsidies, public transportation, etc. and estimating their potential value and benefits, thus ultimately finalising the optimal policy yielding the maximum benefits at the lowest costs.

Shadow pricing is also frequently used in evaluating various projects in the private sector as it helps management assess the value of certain operations and attempts to place a monetary value on the different tasks associated with the project.

Prices, as the term in economics, has two properties. First, it serves as the rate at which the commodities are exchanged in the market, and second, it is a determinant that decision-makers use in deciding which course of action to pursue. Shadow prices possess the second characteristic but not necessarily the first. Shadow prices for use in planning and evaluating public projects are intended to serve as the basis for decisions on the design, adoption, and ultimate operation of these projects, even though they are not necessarily the prices the government pays or receives for inputs used or outputs produced.

Regardless of the abstract and ambiguous nature of shadow prices, they serve as a vital component in policy analysis by quantifying the social benefits of such policies which are otherwise qualitative, for instance, the benefit obtained by constructing public parks, implementing a gender-inclusive employment policy, etc.

Basic Mathematics Behind Shadow Prices

In economic terms, Shadow prices can be seen as the Opportunity Cost of making a choice. Opportunity cost, in simple terms, is the cost of the next best alternate choice available to the decision-maker. For instance, the opportunity cost of building a road may be the cost foregone to build schools.

However, as we dig deeper, the concept of shadow price has a very interesting mathematical interpretation that revolves around linear programming models.

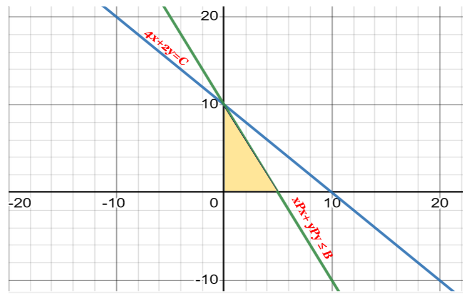

Consider a simple linear programming problem with the objective and constraint functions defined as follows:

Min C(x,y) = 4x+2y

Subject To – x.Px+ y.Py ≤ B

which corresponds to minimizing the costs of producing two goods x and y subject to their given prices and a budget of ‘B’ dollars. Suppose, (x*, y*) is the optimal output combination that does so.

One might wonder what happens to this minimum cost when the budget of the producer increases from B to a higher value. This is exactly the kind of question that shadow prices answer. They highlight the dependency of the objective function on the resource constraints by measuring the changes in the optimum value of the objective functions in response to an additional unit of the resource employed. More specifically, they are computed as the derivative of the objective function concerning the right-hand side of the constraint function which usually corresponds to the resources. In our particular example, the shadow price can be calculated as the derivative of C concerning B. (dC/dB)

Applications in Finance

Shadow pricing plays a crucial role in financial decision-making by providing a mechanism to estimate the monetary and economic value of goods, services, or factors that do not have explicit market prices. The estimations form a benchmark for further impact assessment and decision-making. Its applications are diverse and extend to various areas within finance, including risk management, project evaluation, and resource allocation for organisations. Let’s see how shadow pricing is applicable in these areas:

Under Risk Management:

- Valuing Risks and Uncertainties: Shadow pricing assigns a monetary value to risks and uncertainties associated with financial decisions. It can include risks related to market volatility, interest rate fluctuations, and other uncertainties that may impact the financial performance of an investment or project. Valuing risk gives a broad overview of the financial decisions and risk acceptance appetite.

- Insurance and Hedging against Downsides: When evaluating insurance or hedging strategies, shadow pricing helps quantify the potential losses or gains associated with various risk management instruments. An estimated metric value helps investors and organisations to include policies according to their risk appetite. It enables organisations to make informed decisions and apply risk mitigation strategies.

- Scenario Analysis: Shadow pricing is employed in ‘scenario analysis’ to model the financial impact of different risk scenarios. Scenario analysis is a process that involves examining and evaluating probable future events and predicting possible outcomes for effective decision-making. Scenario analysis is extensively applied in financial modelling, business planning and portfolio valuation, impacting the company-client relationship dynamics.

Under Project Evaluation :

- Environmental and Social Impact Assessment: In project evaluation, especially in sectors with externalities like environmental or social impacts, shadow pricing helps incorporate these non-market factors into the analysis and encourages organisations to align with their business values. The rising prominence of Environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) is a set of considerations, including environmental issues, social issues and corporate governance in investing. It is crucial for assessing the economic viability of a project.

- Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Analysis: The discounted cash flow(DCF) analysis, in finance, is a method used to value a security, project, company, or asset using the quantitative method of time value of money. This valuation method presents the present value production of a company, an asset or security by estimating its future cash flows. Shadow pricing integrated into DCF analysis can account for intangible factors that may affect the project’s cash flows and alter the valuation of the asset, security or the company. It includes considerations such as brand value, reputation, or environmental sustainability. It fosters less information asymmetry for the client and the organisation, as the former can assess several important metrics to make an informed investment.

- ‘Real Options’ Valuation: A real option is a right but not an obligation to accept or make some choices about business projects or investment opportunities. If it does not achieve the economic impact proposition that the company requires, it can be rejected. It derives its name from the concept that the securities and assets traded under these contracts are tangible(such as machinery, land, buildings, and inventory) instead of a financial instrument, thus differing from financial options contracts traded on derivatives or underlying assets. Shadow pricing is used in ‘real options valuation’ when projects with flexibility and uncertainty are evaluated. It helps estimate the value of managerial flexibility in adapting to changing market conditions or unforeseen events.

Under Resource Allocation:

- Optimising Resource Use: Shadow pricing aids in optimising the allocation of resources by assigning values to factors that may not have accurate market prices. It includes human capital, environmental resources, and other intangibles. These contribute to an organisation’s overall productivity and success. It helps to categorize resources according to the organisation’s priority of costs, importance and efficiency.

- Capital Budgeting: When making investment decisions, shadow pricing helps incorporate the impact of externalities or intangible benefits into capital budgeting analyses. Capital budgeting is a process that businesses use to evaluate potential investments or projects. It ensures that investment decisions reflect the broader economic consequences and the organisation’s values and priorities. It’s a long-term plan that outlines the financial needs of an investment, development, or major purchase.

- Policy Formulation: Governments and public policy organisations use shadow pricing to formulate policies that account for externalities in a justified manner. An externality is a cost or benefit a producer causes for others’ consumption but does not financially incur or receive the benefit. Externalities can be positive or negative and can come from the production or consumption of a good or service. Shadow pricing is a vital tool organisations use to put a cost to the externalities caused by them, whether positive or negative. For example, carbon pricing is a form of shadow pricing that aims to reduce carbon emissions by penalising organisations that exceed their carbon credit limit and pollute the environment. It acts as a way of compensating for this environmental degradation. It also incentivises these organisations to adopt sustainable and environment-friendly operating procedures.

Addressing Market Gaps

The economic evaluation of a proposed project involves defining the requirements and attributes of a project and then measuring these attributes in quantitative terms. Market Prices determined by the forces of demand and supply, are a common unit of measurement used for this purpose.

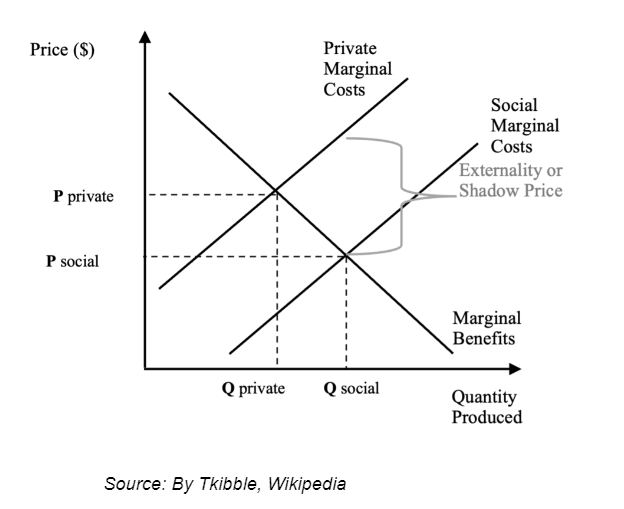

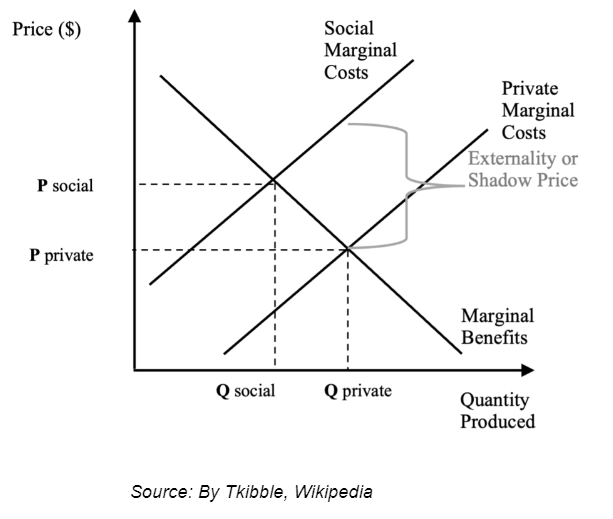

Figure 1: Illustrates the presence of a positive shadow price. In this case, production should increase to meet the socially optimum equilibrium.

For instance: if a public infrastructure project involves building a children’s park, the land, labour and input requirements can simply be stated in terms of their domestic prices and its benefits can be valued in terms of the potential revenue that can be generated by, say, charging an entry ticket for the same. This sounds perfectly applicable in theory, doesn’t it? However, there are many reasons why market prices may be distorted and thus, may not serve as a good tool for quantitative analysis, especially for developing countries. Such reasons can be stated as follows:

- Non-Competitive Behaviour: The majority of the economic analysis is based on an underlying assumption that markets are perfectly competitive. However, in practice, this is quite a far-fetched assumption as most markets do not exist in perfect competition. There are many market conditions in reality such as monopolies, oligopolies, etc, where the firms do not take prices as given and have control over their determination due to which market prices tend to lose their value.

- Disequilibrium in the Labor Market: In less-developed and developing economies, mass unemployment exists at the existing wage rates. Additionally, the presence of the unorganised sector is huge, due to which there is a striking difference between the equilibrium wage rates and the actual wages given to the workers which creates a need for adjustments in such rates.

- Externalities: Externalities are hidden costs and benefits that affect people who are not directly involved in producing or consuming a good/service. Externalities lead to market distortions as the prices do not tend to reflect the actual costs and benefits. For instance, the cost of using coal and petroleum for production does not include the associated hidden environmental costs.

- Government Policy Effects: Government policies such as price ceilings, wage floors, subsidies, etc. are quite common, specifically in developing countries. This is another reason why market prices do not reflect the true market conditions.

Figure 2: Illustrates the presence of a negative shadow price. In this case, production should decrease to meet the socially optimum equilibrium.

These reasons along with many more are sufficient to challenge the practicality of market prices for cost-benefit analysis. Shadow prices help in addressing these market gaps by taking into account such distortions and thus, prove to be a better tool for valuation.

Challenges and Considerations

Implementing shadow pricing comes with several challenges, including data limitations and uncertainties in dynamic market environments. Organisations have to maintain a flexible strategy for a comprehensive utilisation of appropriate resources. Discussed below are some potential challenges faced by organisations with solutions to navigate and mitigate them:

The Challenges:

- Data Limitations

- Nature of Intangibles: Data on intangible factors, such as brand value, reputation, social impact, or environmental benefits, can be challenging to quantify and measure accurately with verity and assurance.

- Lack of Historical Data: Some externalities or non-market factors may lack historical data, making it difficult to establish reliable benchmark values for shadow pricing.

- Unverifiable Data: In addition to data deficiency, the verification and verity of the data affect the estimations. Authentic data is limited and is accessible after incurring extra costs and payments.

- Uncertainties

- Future Predictions: Estimating the future impact of externalities or intangibles involves uncertainties. Economic, social, or environmental conditions may change, affecting the accuracy of predictions. With the rampant dynamic environmental and world order, accurately predicting any future instances, prices and course of action is tenuous and unlikely.

- Behavioural Uncertainties: Human behaviour and market dynamics are inherently uncertain, making it challenging to predict how individuals or markets will respond to shadow pricing.

Navigation and Mitigation:

- Invest in Data Collection and Analysis: Organisations should invest in robust and authentic primary and secondary data collection methods to gather relevant information on non-market and intangible factors. This may involve utilising surveys and questionnaires, already existing literature and reports, and advanced analytics, and collaborating with experts in relevant fields.

- Utilise Interdisciplinary Approaches: Adopting interdisciplinary approaches that involve collaboration between economists, environmental scientists, social scientists, financial analysts, data scientists and other relevant experts. This can enhance the understanding of complex externalities and improve the accuracy of shadow pricing with minimum variabilities and discrepancies in data and its results.

- Education and Training: Organisations should focus on the learning, development and augmenting the research abilities of their employees; involved in the capacity of decision-makers and analysts involved in the implementation of shadow pricing, through education and training. This ensures a clear understanding of the methodology, its limitations, and the ways to navigate uncertainties and handle risk.

- Collaboration with Research Institutions: Collaborating with experienced research institutions and industry associations; informed and equipped with the latest software and methodologies to carry out research, and to stay informed about emerging methodologies and best practices in shadow pricing. Engaging with the broader academic and professional community can bring fresh perspectives and insights, and promote collaboration.

Controversies and Criticisms

Shadow Prices, like all other things, come with their own set of flaws. Having discussed the usefulness and significance of shadow pricing, let’s now review a few criticisms that make this concept controversial.

- Accuracy: Economists question the accuracy of shadow prices as they are based on subjective and sometimes, vague arguments. Additionally, they are based on rather qualitative aspects which are difficult to measure due to their very abstract nature. And if the estimates of such prices are wrong, it could lead to faulty judgements on the part of decision-makers.

- Element of Bias: Since the concept of shadow prices is based on subjective arguments, the presence of the element of bias and judgment is quite plausible. This further challenges the concreteness of shadow prices as assumptions and judgments vary from person to person.

- Informational Failure: The concept of shadow prices assumes the complete availability of information and data which aids the process of calculation. However, adequate data may not be easily available, especially in under-developed and developing economies, which acts as a barrier to computation and destroys the relevance of shadow pricing altogether.

- Calculation complexities: The real-life calculation of shadow prices involves typical and intricate mathematical analysis and computation. This makes the decision-making process complicated and cumbersome. However, the availability of efficient data-analysis tools and statistical software helps overcome this limitation by making this process easier.

- Time Dimension: Shadow prices reflect the social opportunity cost generally for shorter periods, and are argued to lack longevity. This is because of the dynamic market conditions which cause the market prices and other variables to change constantly. Also, since investment projects are devised for longer periods, this aspect further questions the effectiveness of shadow prices.

Despite these limitations, shadow pricing if used with careful consideration of its limitations, can serve as a valuable tool for making informed decisions.

Shadow Prices in Effect: Carbon Pricing

Carbon and carbon-based products such as polymers, pharmaceuticals, solvents, fertilisers and the like, are indispensable components of production in any industry. Having stated its importance, carbon is the main contributor to the emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs), which have their external costs associated with them like damage to crops, health care costs from heat waves and droughts, and loss of property from flooding and sea level rise.

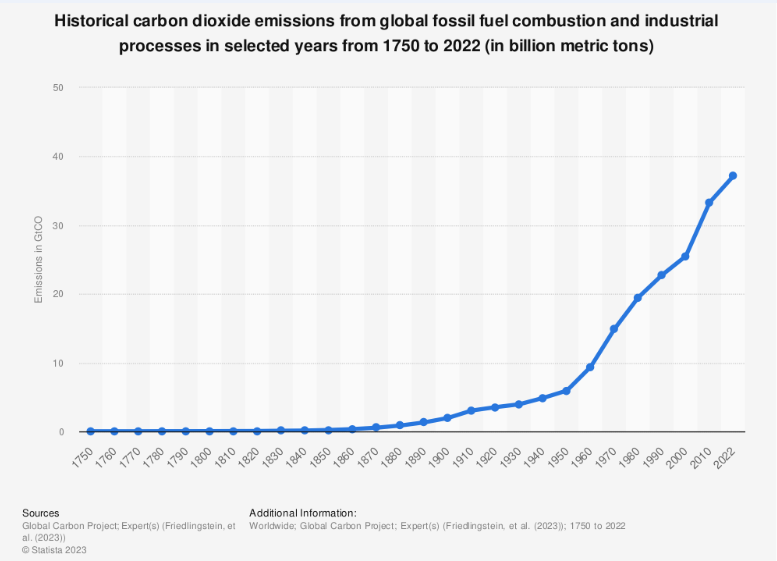

We see the rise in the emission of carbon dioxide emissions from 1750-2022 has been exponential, the latest figures being close to 39 billion metric tons in 2022. This explosive rise in carbon dioxide emissions with raising concerns about climate change and climate activism has given rise to the concept of Shadow Carbon Pricing.

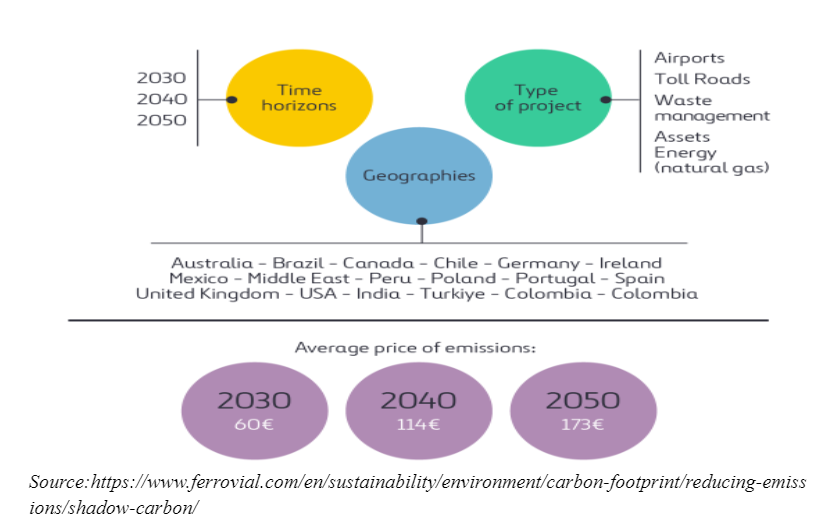

Shadow Carbon Pricing is a methodology that quantifies risks and opportunities for new investments in CO2 emissions, created based on the recommendations of the Paris Agreement to establish carbon prices.

The Paris Agreement of 2015 was a critical point for international climate action and its importance. For the first time, all nations came together in the common cause of combatting climate change. The Agreement aims to limit the global temperature rise to below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and also encourages efforts to limit the temperature increase even further, to 1.5 degrees Celsius. To achieve these ambitious goals the Agreement sets out provisions for enhanced cooperation among the developed, developing middle-income, and the least developed nations, on climate change mitigation, including through market-based approaches, such as carbon pricing.

Carbon pricing is an instrument that captures these external costs of GHG emissions by levying a fee on emitting or offering an incentive to reduce their impact on the environment. Thus, instead of dictating who should reduce emissions where and how, a carbon price provides an economic signal to emitters, and allows them to decide to either transform their activities and lower their emissions, or continue emitting and paying for their emissions.

“Shadow Carbon Pricing takes into account different factors such as the economic cost of carbon emissions, the taxes applied to fossil fuels, and changes in user usage, oriented towards new habits and demands by society.”

According to research carried out by ‘Ferrovial’(one of the world leaders in infrastructure in collaboration with the renewable sector), “The average carbon price is expected to rise from 60 euros in 2030, 114 euros in 2040 and 173 euros in 2050. These increases are related both to decarbonization to avoid abrupt climate change and to end-users’ perception of the company’s ethical policies.

The working methodology goes beyond a constant measurement of CO2 emissions associated with each project; the idea is to account for and translate into a monetary value the environmental and social perception cost of these emissions in a growing total (2020, 2030, 2040, 2050). In this way, the risks associated with climate change are faithfully reflected, allowing us to identify short-, medium- and long-term risks.”

For this policy to be effective, it is of utmost importance that such prices are measured most effectively and accurately. It is where shadow prices come into effect. A shadow price on carbon creates a theoretical or assumed cost per ton of carbon emissions. It explains the potential impact of external carbon pricing on the profitability of a project, a new business model, or an investment. The observed price range for companies using an internal carbon fee ranges from $5-$20 per metric ton.

By using shadow prices to quantify the hidden costs associated with carbon usage, the overall environmental goal is achieved in the most flexible and least-cost way in society.

Technological Innovations

Technology has advanced shadow pricing methodologies. It has increased accuracy and efficiency in estimating the economic value of non-market factors and intangible assets. With the advent of Artificial Intelligence, humanoid robots and LLM models, there are many technological tools to assist us in complex tasks. We discuss the role of technology and some specific tools or innovations that enhance shadow pricing:

- Data Analytics and Machine Learning: Advanced data analytics and machine learning algorithms help process vast amounts of data quickly and identify patterns with greater accuracy that may be challenging to detect manually.

These technologies enhance the accuracy of shadow pricing by allowing organisations to analyse large, complex and interconnected datasets, identify relevant variables, and make more nuanced predictions about the economic impact of externalities and gain insights to minimise them.

- Blockchain Technology: Blockchain technology ensures transparency, immutability, and data traceability. It works without a central authority and allows the creation of a decentralised and immutable ledger of verifiable and traceable transactions. Shadow pricing can securely record and verify transactions related to externalities.

Blockchain enhances data reliability, reduces the risk of fraud, and improves accuracy by providing a secure and transparent ledger for recording relevant information.

- Remote Sensing Technologies: Technologies such as satellite imagery and remote sensing provide real-time data on environmental conditions, enabling organisations to monitor changes and assess the impact of activities on natural resources more accurately and with more personalisations.

Remote sensing is information acquisition about an object or phenomenon without making physical contact with the object. Remote sensing technologies contribute to more accurate shadow pricing by providing timely and detailed information on environmental externalities. It is particularly relevant in agriculture, forestry, and land use.

- Big Data Platforms: Big data platforms enable organised storage and analysis of large and complex datasets. They facilitate the integration of diverse data sources, including structured and unstructured data to process further.

Big data platforms enhance the efficiency of shadow pricing methodologies by accommodating the diverse data sources relevant to non-market factors. They enable a more comprehensive information analysis, leading to more accurate shadow prices.

Technological advancements have eased out many constraints and information asymmetry while dealing with shadow prices. This has proved to be beneficial for numerous organisations and their operations.

Conclusion

Shadow Pricing is a vital tool in modern economic decision-making, offering a mechanism to assign monetary values to intangible or non-market factors. We underscore its importance in conducting cost-benefit analyses, particularly in scenarios where traditional market prices may not accurately reflect the true economic value.

In essence, shadow pricing bridges the abstract and the tangible, offering a means to quantify the unquantifiable. Carbon pricing, the act of pricing carbon emissions in the environment as a negative externality, is a major step towards sustainable and responsible shadow pricing practices.

As businesses and policymakers navigate the complexities of a rapidly evolving economic landscape, the judicious use of shadow pricing with technological advancements can foster more informed and economically sound decisions.

References:

- Hayes, A. (2021, September 25). Shadow Pricing: Definition, How It Works, Uses, and Example. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/shadowpricing.asp

- Corden, W. M., Dasgupta, P., & Harberger, A. C. (2002, March 23). Shadow prices, market prices and project losses. Economics Letters. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/016517657990051X

- Lenzu, S., & Manaresi, F. (2022, March). The Cost of Shadow Cost of Capital. https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~slenzu/Papers/Shadow_Costs_LM.pdf

- WallStreet Mojo. (n.d.). Shadow pricing (definition, examples) | how it works? (n.d.) – wallstreetmojo. https://www.wallstreetmojo.com/shadow-pricing/

- Kwatiah, N. (2016, March 2). Shadow Prices: Meaning, Need, Limitations and Uses. Economics Discussion. https://www.economicsdiscussion.net/price/shadow-prices/shadow-prices-meaning-need-limitations-and-uses/18887

- Warr. (1974, October). THE ECONOMICS OF SHADOW PRICING: MARKET DISTORTIONS AND PUBLIC INVESTMENT. University of Minnesota. Retrieved January 21, 2024, from https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNAAA965.pdf

- Cultural Influences on Financial Decisions. (n.d.). https://www.managementstudyguide.com/cultural-influences-on-financial-decisions.htm

- CARBON PRICING: Setting an internal price on carbon | The Gold Standard. (n.d.). https://www.goldstandard.org/blog-item/carbon-pricing-setting-internal-price-carbon#:~:text=An%20internal%20or%20shadow%20price%20on%20carbon%20creates,model%2C%20or%20an%20investment.%20This%20reveals%20hidden%20risks.

- What is Carbon Pricing? | Carbon Pricing Dashboard. (n.d.). https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/what-carbon-pricing

- Internal Carbon Pricing – Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. (2017, October 29). Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. https://www.c2es.org/content/internal-carbon-pricing/#:~:text=The%20observed%20price%20range%20for%20companies%20using%20an,prioritize%20low-carbon%20investments%20and%20prepare%20for%20future%20regulation.

- Shadow price. (2023, December 6). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shadow_price

- (n.d.). Shadow Carbon Pricing. Ferrovial. https://www.ferrovial.com/en/sustainability/environment/carbon-footprint/reducing-emissions/shadow-carbon/

- (n.d.). About Carbon Pricing. United Nations Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/about-us/regional-collaboration-centres/the-ciaca/about-carbon-pricing

- Bennett, V. (2019, January 23). What is shadow carbon pricing? European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. https://www.ebrd.com/news/2019/what-is-shadow-carbon-pricing.html