Climate change has pushed both insured and uninsured disaster losses to consistently high levels. Now, “secondary perils,” such as floods, storms, and wildfires, drive year-to-year changes. Traditional catastrophe models, which rely on long historical records and slowly changing hazard assumptions, struggle to keep up with changing climate dynamics, rapid exposure growth, and regulatory and affordability issues. This paper brings together evidence from the global and Indian markets on the economics of climate risk in insurance. It covers loss trends, pricing cycles, reinsurance capacity, protection gaps, regulatory responses, and the limits of current models. Case studies from the U.S. wildfire and coastal markets, the U.K.’s Flood Re, and India’s monsoon floods and crop insurance show where outdated approaches fail and what approaches are effective. We argue that the traditional model can only survive by evolving quickly. It must integrate changing hazards, forward-looking scenarios, adaptive pricing, public-private risk sharing, prevention incentives, and data and AI systems that effectively improve the combined ratio.

THE ECONOMICS OF CLIMATE RISK: LOSSES, CAPITAL, AND AFFORDABILITY

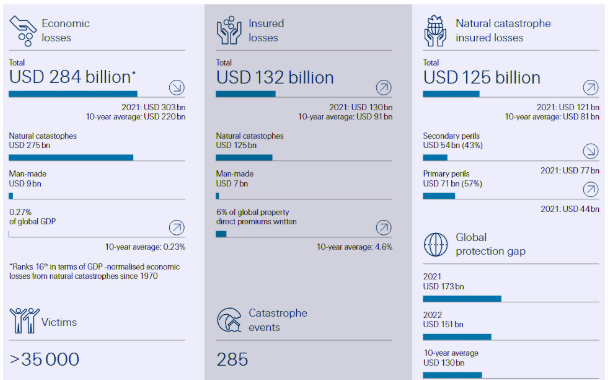

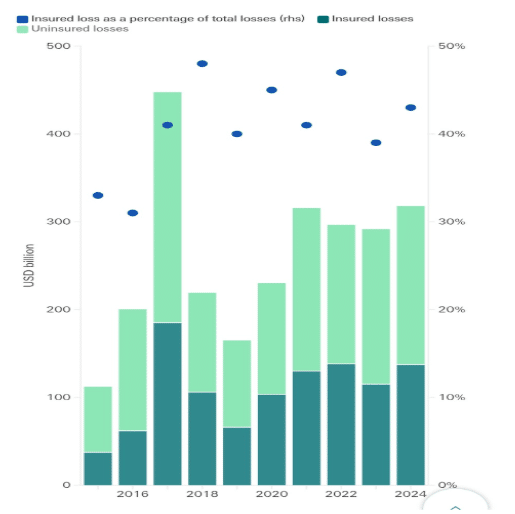

In recent years, losses from insured natural disasters have remained high, driven by increased hazard activity and a greater concentration of exposure in vulnerable areas. Recent reports from Munich Re and Swiss Re indicate that global annual economic losses from natural catastrophes average between USD 250 billion and USD 300 billion. Typically, insured losses make up USD 100 billion to USD 150 billion of that total. These statistics highlight a consistent trend of significant loss activity, even in years without major peak events like large hurricanes in the U.S. or earthquakes in Japan.

A key aspect of the current loss landscape is the rise of secondary perils, which are smaller but more frequent incidents such as severe storms, urban flooding, wildfires, and hailstorms. Once considered insignificant, these events now account for most insured losses worldwide. The U.S. has seen a surge in severe storms, leading to repeated billion-dollar insurance payouts over several months. Europe has experienced more severe flooding due to urban development, saturated soils, and changing rainfall patterns. Meanwhile, Asia is dealing with increased flooding from typhoons and monsoons, worsened by coastal development and inadequate drainage systems.

This ongoing environment of high losses has created a hard reinsurance market since 2023. Reinsurers, facing increased volatility and tighter capital conditions, have raised prices, narrowed coverage options, and required higher retentions from cedants. These stricter terms are passed down, driving up premiums in the primary market. In some cases, insurers have reduced their capacity in high-risk areas or excluded certain perils from coverage. This has led to growing challenges in affordability and availability for policyholders, especially in regions with frequent but moderate losses.

As a result, there is a widening protection gap—the difference between total economic losses and insured losses. On a global scale, only about one-third of catastrophe losses are covered by insurance, meaning that two-thirds of economic losses are borne by governments, businesses, and households. In emerging markets, this percentage can drop below 10%, leaving entire economies fragile after disasters and slowing recovery efforts. Organizations like the Geneva Association, the European Central Bank, and the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority have warned of wider economic repercussions as climate threats grow without a corresponding rise in insurance coverage. These repercussions appear through declining asset values, fiscal burdens on public finances, and weakened banking stability in disaster-prone areas.

At the same time, capital markets have stepped in to help counter the limited supply of reinsurance. The market for insurance-linked securities, including catastrophe bonds and collateralized reinsurance, reached record levels of issuance in 2024 and 2025, increasing overall capacity to unprecedented heights. This alternative capital has provided a vital buffer, allowing cedants to manage risk beyond traditional reinsurance and lessen their reliance on capacity from high-risk areas. However, insurance-linked securities can be sensitive to events and cyclical in nature.

Following major loss years, spreads often widen sharply due to investor caution and the limited liquidity of this asset class. While these instruments provide additional capacity, they do not address the fundamental issues of pricing or coverage availability in areas where risk is poorly understood, climate models are uncertain, or local premiums are too high for affordability.

The ongoing combination of high loss experiences, expensive capital, and increased uncertainty around modeling creates a cycle that pushes premiums higher, tightens underwriting guidelines, and raises the cost of protection for both households and businesses. For many risks, especially in flood and fire-prone areas, private insurance is nearing an unsustainable level without government intervention or large-scale efforts to manage risk. This situation has sped up the growth of residual market mechanisms, such as publicly backed pools or “insurers of last resort” like the U.S. National Flood Insurance Program and California’s FAIR Plan. While these programs help maintain some coverage availability, they also introduce fiscal and moral hazard risks if not managed with effective pricing and proactive measures.

From both an actuarial and policy perspective, these forces highlight the need to shift focus from post-loss funding to pre-loss risk reduction. Simply hiking premiums in response to heightened hazard levels might protect solvency in the short term but could drive more participants out of the insurance pool, further widening the protection gap. To find sustainable solutions, a multi-faceted approach is necessary:

- Invest in infrastructure for mitigation and adaptation (e.g., flood defenses, resilient buildings, wildland fire safety zones).

- Develop better catastrophe modeling frameworks that use climate data and account for related risks.

- Foster public-private partnerships that combine insurance, reinsurance, and government risk finance.

- Allow regulatory flexibility for recognizing long-term capital invested in mitigation and resilience.

- Increase data-sharing between insurers, reinsurers, and public agencies to enhance hazard mapping and exposure accuracy.

In summary, the insurance and reinsurance sectors are facing a structural challenge rather than a fleeting issue. Rising catastrophe losses, limited capital, and increasing climate unpredictability are reshaping pricing, availability, and capital management. Unless risks are addressed at their source rather than just being repriced, the global protection gap will continue to widen. This will not only increase financial losses but also heighten social and economic vulnerability in a warmer, more hazardous world.

WHY TRADITIONAL CAT MODELS STRUGGLE

Classic catastrophe (cat) models rely on the assumption of statistical stationarity, meaning that historical hazard frequencies, severities, and spatial distributions are seen as indicators of future risks. This assumption has allowed insurers, reinsurers, and actuaries to create models based on decades of weather and loss data. In essence, patterns from the past were viewed as reasonable guides to future risks.

However, the changing nature of the climate is gradually undermining this assumption. Human-induced warming has affected how natural disasters behave, their intensity, and their clustering. This creates serious challenges for cat modeling and risk pricing. Changes in atmospheric and ocean currents are altering how storms form, their paths, and their strengths. Wildfire patterns are also shifting due to hotter and drier conditions, leading to longer fire seasons and more frequent “mega-fires.” Changing rainfall patterns, snowmelt schedules, and land-use changes are reshaping flood risks. The emergence of compound events, such as tropical cyclones followed by inland flooding or heatwaves during droughts, complicates the interaction of hazards and loss modeling.

Research and findings from actuaries and catastrophe modeling groups have pointed out various aspects of the problem. There are gaps in data, such as insufficient detail on perils, inconsistent historical loss records, and a lack of local exposure or condition data, like building age, material strength, and vegetation density. Challenges also exist in model structure and calibration. Many models were built to extrapolate from past distributions rather than simulate new climate behaviors. Therefore, projections may not account for future volatility and the changing relationships between different risks.

Regulators are concerned as well. Organizations like the Bank of England’s Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) and the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) have pointed out flaws in insurers’ internal models. These include incomplete exposure data, poor representation of physical climate risk, and too much reliance on looking backward. The lack of precise exposure mapping hinders both capital adequacy assessments and accurate modeling of localized hazard intensity.

From an actuarial perspective, the challenge has two parts. First, the frequency and severity of insured losses are no longer stable. The old assumption that these factors can be determined from historical data and adjusted for inflation or growth is increasingly unreliable. Non-linear feedbacks in climate systems could lead to sudden shifts in return periods and loss probabilities, making past calibration less dependable.

Second, correlations between different perils and regions are increasing, especially in warmer years. Historically, cat perils were often modeled as somewhat independent, such as European windstorms and North Atlantic hurricanes. However, the observed connection between perils, like simultaneous droughts and wildfires across continents or multi-basin storm anomalies related to ENSO, creates stronger dependencies. This leads to higher overall risk and, consequently, greater capital demands under solvency rules like Solvency II or the Swiss Solvency Test.

The outcome is a more unpredictable underwriting environment. Pricing models that depend on short-term loss histories, common in areas like severe convective storm (SCS) insurance, result in cycles of rapid changes: periods of underpricing during calm years followed by sharp premium increases after seasons with heavy losses. These cycles lead to economic inefficiencies as capital gets misallocated and raise political tensions, especially when public affordability or availability of coverage is in question.

REGULATORY AND SUPERVISORY RESPONSES (GLOBAL)

- Disclosure and risk management. NAIC (U.S.), PRA (U.K.), and EIOPA (EU) have pushed insurers toward TCFD/ISSB-style disclosures, scenario analysis, and the integration of physical and transition risks in ORSA and Solvency frameworks. PRA’s recent review identified major weaknesses and established timelines for fixing them.

- Public-private risk sharing. Europe’s central banking and insurance supervisors suggest a bloc-wide public reinsurance and disaster funds to reduce the protection gap and encourage private coverage.

- Program reform. The U.S. flood program (NFIP) is transitioning to Risk Rating 2.0, which offers more detailed and consistent risk rates. This aims to restore financial stability and shift incentives toward mitigation, although the politics around affordability are still very heated.

INDIA’S POLICY ARCHITECTURE IS CATCHING UP

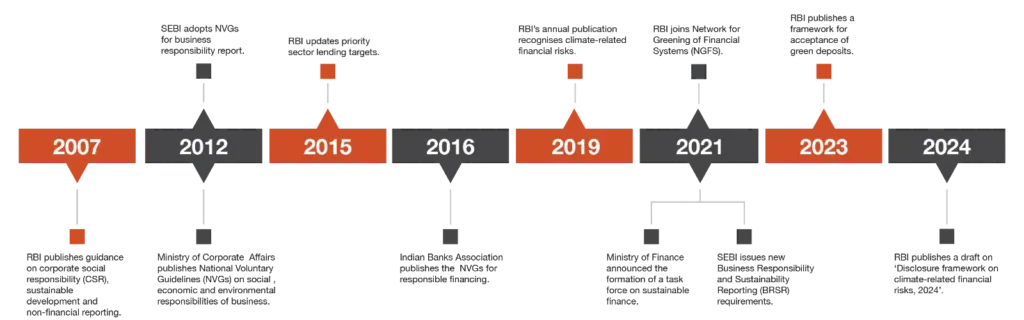

Source:https://www.pwc.in/blogs/disclosure-framework-on-climate-related-financial-risks-2024.html

- RBI climate-risk disclosure framework. India’s central bank (RBI) issued a Draft Disclosure Framework on February 28, 2024, aligned with TCFD. Final rules are expected to phase in governance, strategy, and risk management disclosures from FY2026 and metrics and targets by FY2028. This applies to banks and NBFCs; insurers engage through their asset side and groups. It aims to improve transparency and allow supervisors to conduct systemwide climate analysis.

- SEBI BRSR / BRSR-Core. The top 1000 listed entities must produce Business Responsibility and Sustainability Reports. Assurance will phase in, along with Scope 3 for top cohorts. This will indirectly improve data quality for insurers, both as investors and as corporate risk underwriters.

- Catastrophe pooling debate. Stakeholders in the Indian market continue to discuss national natural catastrophe pooling and reinsurance solutions. Regulators and public reinsurers have shown interest due to the volatility from monsoon and flood losses. However, formalized and broad catastrophe pooling is still a work in progress.

CASE STUDIES

1.U.S. homeowners insurance under climate stress (California & Florida)

In California, wildfire-exposed ZIP codes face insurer retrenchment and moratoria; in Florida, elevated reinsurance costs and litigation history translated to premium spikes and insurer exits, pushing more policies to state residual markets;classic symptoms when risk isn’t mitigated enough to price sustainably. Academic and Fed working papers show regulation can decouple rates from risk, creating cross-subsidies that backfire as hazards intensify.

Economic takeaway: Without mitigation and risk-reflective pricing, capital flees, supply shrinks, and affordability worsens;shifting burden to taxpayers via residual markets.

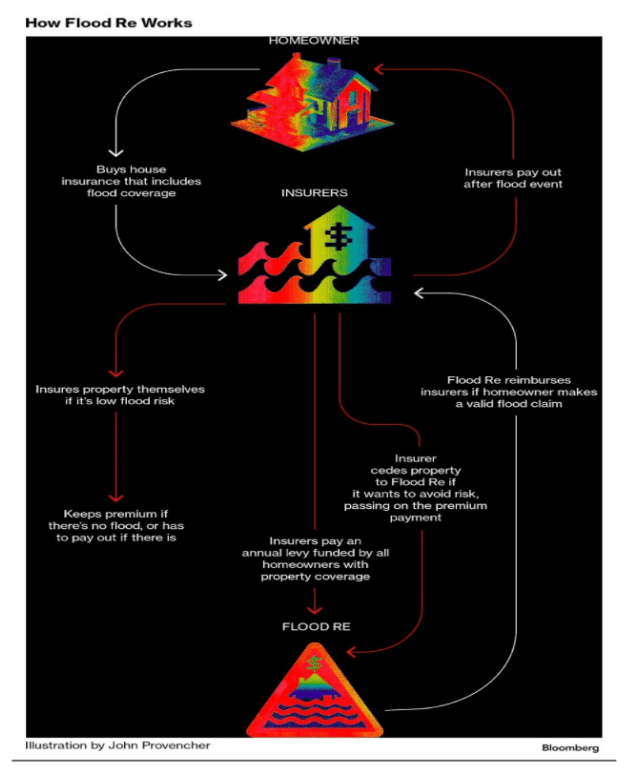

2. U.K. Flood Re: buying time while paying for resilience

Flood Re;an industry-funded, government-backed reinsurance scheme;has kept high-risk homes insurable while the scheme drives Build Back Better (BBB) grants up to £10,000 for property flood resilience post-claim. Ceded policies hit a record 346k in 2024/25; over 70% of the home market offers BBB options. This is a pragmatic bridge model with an exit date (2039) to avoid permanent subsidy drift.

Economic takeaway: Pairing reinsurance support with mandated resilience investment materially improves loss cost trajectories, maintaining private insurance at tolerable price points.

3.India’s 2023–25 monsoon losses & the Himalayan test

Himachal Pradesh’s July 2023 disaster;days with >400% of normal rainfall;triggered landslides/flash floods with damages estimated into the ₹10,000 crore range by various assessments, with recurrent losses again in 2024–25. These are emblematic of compounding risks (topography + intense rain + land-use).

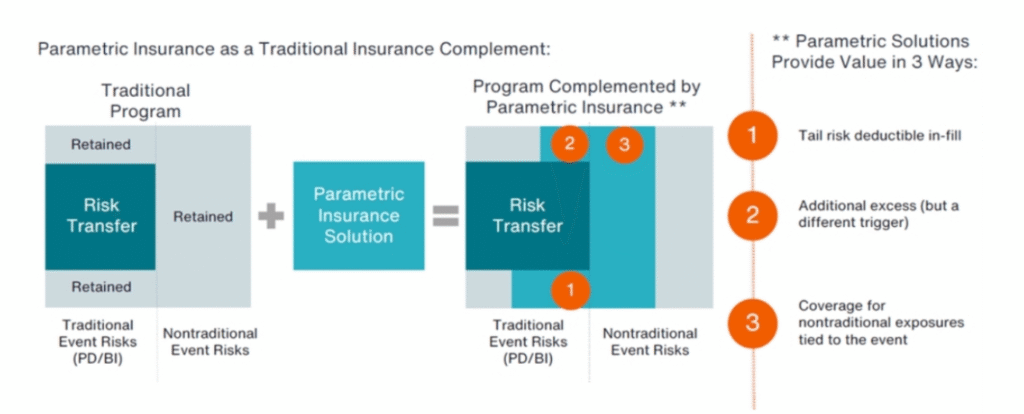

Insurance lens: Urban flood coverage and SME BIs remain thin; micro and parametric pilots (e.g., Nagaland’s district-level rainfall parametric) show promise for rapid liquidity and lower basis risk when designed with dense local data. Scaling such tools across flood/heat/cyclone belts can buffer livelihoods while primary insurers manage accumulation via parametric/reinsurance stacks.

4.Agriculture: PMFBY and climate volatility

India’s PMFBY has expanded farmer coverage and paid sizable claims in severe seasons; yet drought/flood clustering and assessment frictions keep loss ratios lumpy and fiscal outlays uncertain. Embedding parametric triggers for certain perils and incentivizing heat/flood-smart agronomy could improve cost predictability and timeliness of payouts.

PRICING, CAPITAL, AND MODEL EVOLUTION: WHAT ACTUALLY HAS TO CHANGE

1) From stationarity to adaptive, scenario-linked pricing.

Shift from a single “best estimate” view to a mix that includes: (i) updated catastrophe models combined with climate changes; (ii) physics-informed hazard shifts (such as SCS environments and ENSO-related flood risks); and (iii) supervisory climate scenarios (like NGFS) for multi-decade perspectives in ORSA and capital planning. PRA, EIOPA, and global actuarial groups strongly support this integration. Firms that don’t adapt will misprice and under-reserve.

2) Data pipelines over model gloss.

The main issue is often exposure and condition data, such as accurate geocoding, first-floor heights, defensible space for wildfires, and roof features. PRA found that many firms lack even basic geolocation data, which explains why model error margins remain large. India’s BRSR/ISSB initiative and RBI’s climate disclosure will indirectly improve the quality of counterpart data.

3) Dynamic underwriting and product mix.

Risk-reflective pricing, similar to NFIP’s Risk Rating 2.0, increases signal accuracy; affordability should be addressed separately through means-tested credits and resilience grants. The GAO connects NFIP’s past underpricing to structural issues; correcting price signals is crucial.

Source: aon.com

Parametric layers (like rainfall, wind, and heat indices) provide quick payouts, lower loss-adjustment delays, and can quickly provide cash for households, small businesses, and states, especially in India’s monsoon regions.

Prevention-linked benefits (UK’s BBB) improve the economics by reducing expected losses and tail severity.

4) Capital strategy.

Combine traditional reinsurance with ILS to lower risk in high-impact areas and reduce earnings unpredictability. Expect higher retentions and named-peril structures to continue; governments should create backstops that unlock private capacity only where risk-based pricing and mitigation efforts are in place.

5) Public-private partnerships that reward mitigation.

EU plans for public reinsurance and disaster funds along with the UK’s Flood Re demonstrate a workable model: risk-based pricing, targeted social assistance, and mandatory resilience improvements. Applying this approach in India, such as establishing a national flood pool with resilience requirements tied to river-basin planning and urban drainage upgrades, can maintain large-scale private insurance.

THE INDIA PLAYBOOK

- Finalize and expand disclosures. RBI’s climate-risk disclosure should transition from draft to rule with clear timelines for scenario analysis and portfolio heatmaps. Work with IRDAI on insurer-specific expectations to avoid gaps between asset-side oversight (RBI) and liability-side oversight (insurance).

- Pilot a layer similar to India Flood Re. Begin with high-loss urban areas like Mithi, Adyar, and Vrishabhavathi, as well as towns in the Himalayas. Fund this with a sector levy and state contributions. Require resilience projects similar to BBB for claim repairs. Use parametric first-loss to speed up the process.

- Improve data collection. Require information on elevation, roof features, and defensible space when policies start or renew. Use resources from ISRO, IMD, and municipal LIDAR. Link municipal funding to the adoption of flood zoning and upgrades to green and grey drainage. PRA’s findings show the risks of blind underwriting.

- Adjust PMFBY for heat and flood changes. Add parametric supplements for extreme heat and humidity, as well as for short-duration heavy rain. Combine agronomic adjustments (sowing windows, resilient crops) with premium credits.

- Include ILS solutions. Standardize disclosure and peril definitions to help support rupee and hard-currency catastrophe bonds, led by GIC, initially sponsored by the state for cyclone and flood events.

CAN TRADITIONAL MODELS SURVIVE?

Yes, but only as part of a modern stack. The old, backward-looking cat model does not meet today’s hurdles. Survivors will:

– Treat stationarity as an assumption to test, not to believe;

– Use ensemble, scenario-based pricing with clear climate changes and error margins;

– Include prevention incentives (like BBB) in coverage;

– Combine reinsurance and ILS to stabilize capital;

– Work with the state for focused affordability and funding for resilience; and

– Fix data issues.

Source: Bloomberg.com

In places where markets tried to keep prices low without reducing risk, like some U.S. states, capacity disappeared and taxpayers had to step in. In contrast, where systems accurately priced risk and funded mitigation, like Flood Re and BBB, availability remained stable. India has an opportunity through RBI/SEBI disclosure updates, urban resilience investment, and parametric scaling to create a sustainable approach for a monsoon-era economy.

References

- Bankrate. “Understanding FEMA’s Risk Rating 2.0 System for Flood Insurance.” Bankrate, updated 2025. https://www.bankrate.com/insurance/homeowners-insurance/flood-insurance-rate-changes/.

- European Central Bank. “ECB and EIOPA Propose European Approach to Reduce Economic Impact of Natural Catastrophes.” ECB Press Release, December 18, 2024. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2024/html/ecb.pr241218~b6df28c7af.en.html.

- European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA). “EIOPA and ECB Propose European Approach to Reduce Economic Impact of Natural Catastrophes.” EIOPA, December 18, 2024. https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/eiopa-and-ecb-propose-european-approach-reduce-economic-impact-natural-catastrophes-2024-12-18_en.

- Federal Reserve Board. “Pricing of Climate Risk Insurance: Regulation and Cross-Subsidies.” FEDS Working Paper (2022-064). https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/pricing-of-climate-risk-insurance-regulation-and-cross-subsidies.htm.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). “NFIP’s Pricing Approach (Risk Rating 2.0).” FEMA. https://www.fema.gov/flood-insurance/risk-rating.

- Flood Re. Flood Re — Reports (including Annual Report and ARA 2025). Flood Re. https://www.floodre.co.uk/about-us/reports/; Annual Report PDF: https://www.floodre.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/Flood-Re-Limited-ARA-2025-FINAL-EY-signed.pdf.

- Flood Re. “Build Back Better — Property Flood Resilience Funding.” Flood Re. https://www.floodre.co.uk/buildbackbetter/.

- The Geneva Association. Understanding and Addressing Global Insurance Protection Gaps. Geneva Association, 2018. https://www.genevaassociation.org/sites/default/files/research-topics-document-type/pdf_public/understanding_and_addressing_global_insurance_protection_gaps.pdf.

- The Geneva Association. “Safeguarding Home Insurance: Reducing Exposure and Vulnerability to Extreme Weather.” Research report and summary (May 2025). https://www.genevaassociation.org/publication/climate-change-environment/safeguarding-home-insurance-reducing-exposure-and. PDF: https://www.genevaassociation.org/sites/default/files/2025-05/safeguarding_home_insurance_140525.pdf.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). “Climate Change.” IMF topic page (overview and links to IMF papers and working papers). https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/climate-change. (See also IMF Working Paper: Central Banks and Climate Change: Key Legal Issues, WP 24/192). https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/WP/2024/English/wpiea2024192-print-pdf.ashx.

- Munich Re. “Natural disasters 2024 — Factsheet / Natural-cat statistics.” Munich Re (NatCat factsheet and press release), January 2025. PDF factsheet: https://www.munichre.com/content/dam/munichre/mrwebsitespressreleases/MunichRe-NatCAT-Stats2024-Full-Year-Factsheet.pdf. https://www.munichre.com/en/company/media-relations/media-information-and-corporate-news/media-information/2025/natural-disaster-figures-2024.html.

- Swiss Re Institute. sigma 1/2025: Natural catastrophes — insured losses on trend to USD … Swiss Re Institute, 2025. https://www.swissre.com/institute/research/sigma-research/sigma-2025-01-natural-catastrophes-trend.html.

- Bank of England (Prudential Regulation Authority). “CP10/25 — Enhancing banks’ and insurers’ approaches to managing climate-related risks (Consultation Paper and draft supervisory statement),” April 30, 2025. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/publication/2025/april/enhancing-banks-and-insurers-approaches-to-managing-climate-related-risks-consultation-paper. Appendix/SS: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/prudential-regulation/consultation-paper/2025/april/cp1025-appendix.pdf.

- Reserve Bank of India (RBI). “Draft Disclosure Framework on Climate-related Financial Risks, 2024” (press release and draft PDF; RBI press release Feb. 28, 2024). RBI press page: https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx?prid=57408. Draft PDF (mirror / working copy): https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Content/PDFs/DRAFTDISCLOSURECLIMATERELATEDFINANCIALRISKS20249FBE3A566E7F487EBF9974642E6CCDB1.PDF. (Coverage: Reuters summary: https://www.reuters.com/world/india/india-cenbank-releases-draft-disclosure-framework-banks-address-climate-risks-2024-02-28/).

- Reuters. “India cenbank releases draft disclosure framework for banks to address climate risks.” Reuters, February 28, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/india/india-cenbank-releases-draft-disclosure-framework-banks-address-climate-risks-2024-02-28/.

- Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI). “Business Responsibility and Sustainability Reporting (BRSR).” SEBI circulars and BRSR-Core (May 2021; BRSR Core July 12, 2023). https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/circulars/may-2021/business-responsibility-and-sustainability-reporting-by-listed-entities_50096.html; https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/circulars/jul-2023/brsr-core-framework-for-assurance-and-esg-disclosures-for-value-chain_73854.html.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). Flood Insurance: FEMA’s New Rate-Setting Methodology Improves Actuarial Soundness but Highlights Need for Broader Program Reform. GAO-23-105977 (report and PDF). https://www.gao.gov/assets/830/828044.pdf.

- Ingels, Michiel W., W. J. Wouter Botzen, Jeroen C.J.H. Aerts, Jan Brusselaers, and Max Tesselaar. “The State of the Art and Future of Climate Risk Insurance Modeling.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (2024). Full text (open access): https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11580769/.

- Mongabay-India. “Monsoon left widespread destruction and uneasy questions in Himachal.” Sept. 2023. https://india.mongabay.com/2023/09/monsoon-left-widespread-destruction-and-uneasy-questions-in-himachal/.

- Mongabay-India. “First payout under extreme-weather insurance triggers relief and intrigue” (Nagaland parametric / first payout), June 20, 2025. https://india.mongabay.com/2025/06/first-payout-under-extreme-weather-insurance-triggers-relief-and-intrigue/. (Background on parametric pilots: https://india.mongabay.com/2024/06/india-experiments-with-parametric-insurance-to-mitigate-costs-of-disasters/).

- Artemis (Artemis.bm). “Catastrophe bond & ILS market statistics and market reports (Q1/Q2 2025 reports & dashboard).” https://www.artemis.bm/dashboard/cat-bond-ils-market-statistics/; market reports: https://www.artemis.bm/artemis-ils-market-reports/.

- Stateline (Pew/Stateline). Alex Brown, “California fires show states’ ‘last resort’ insurance plans could be overwhelmed,” January 16, 2025. https://stateline.org/2025/01/16/california-fires-show-states-last-resort-insurance-plans-could-be-overwhelmed/.

- Time. “Home Losses From the LA Fires Hasten ‘An Uninsurable Future’.” Time, 2025. https://time.com/7205849/los-angeles-fires-insurance/.

- Financial Times / Reuters coverage (examples for EU and nat-cat insurance policy debate): Reuters coverage of ECB/EIOPA proposals and FT analysis. See Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/ecb-proposes-eu-scheme-expand-climate-insurance-uptake-2024-12-18/; FT coverage: https://www.ft.com/content/8a817c1e-dca4-4784-aba3-8cb414e23977.

Recent Comments