Why the Dollar: Context and History

The history of the U.S. dollar’s dominance has undergone significant evolution over the past several decades. In 1971, President Richard Nixon ended the dollar’s gold convertibility, marking the end of the Bretton Woods system and ushering in a floating exchange rate structure. Even though the gold link was severed, the dollar remained the world’s primary currency because of widespread trust, its role in global trade, and the strength of the U.S. economy, which provided stability during uncertain times. The country’s deep and liquid financial markets, particularly treasury bonds, continued to be seen as safe investments by governments and businesses around the world.

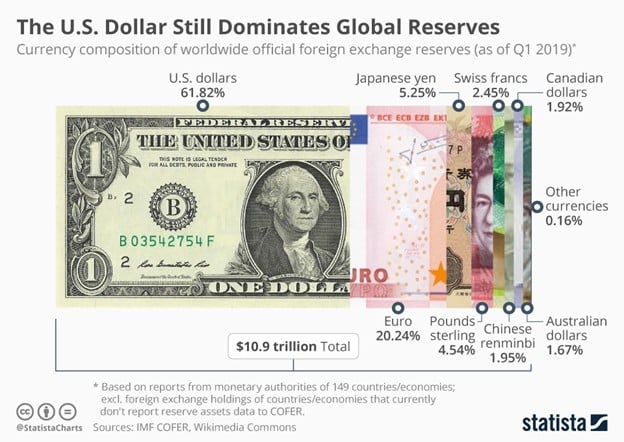

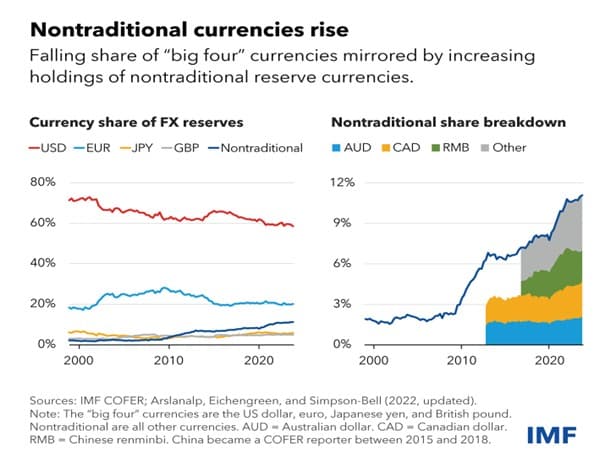

During the 1970s, the dollar’s position was further reinforced when oil-exporting countries agreed to price and trade oil exclusively in dollars, a system now known as the petrodollar. This agreement ensured that nations had to hold and use dollars to meet their energy needs, dramatically increasing global demand. Over the years, not only oil but also other commodities, such as gold, and various trade settlements have become dollar-denominated, embedding the currency at the core of international finance. The U.S. economy’s scale and stability played a major role in maintaining this dominance, with nearly 57.74% of global foreign exchange reserves held in dollars as of 2025, according to IMF COFER data. Moreover, America’s strong geopolitical and military influence encouraged trust and dependence on its currency, while its advanced banking system, efficient payment networks, and extensive capital markets made cross-border trade and investments easier than ever before. As more countries and businesses adopted the dollar, it became even more practical and cost-effective to use, creating a network effect that continues to reinforce its global role and influence today.

The BRICS grouping originated as a concept by Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neill in 2001, recognizing Brazil, Russia, India, and China as rapidly growing emerging economies. Politically, the BRIC countries sought a platform to voice their growing influence and reform international governance systems perceived as Western-centric.

BRICS evolved from informal diplomatic meetings starting in 2006 into a structured summit process by 2009, with South Africa joining officially in 2010 to form BRICS. The bloc integrates economic cooperation, political dialogue, and cultural exchange, aiming to strengthen the emerging economies’ global role and reduce reliance on Western institutions and the US dollar. In recent years, BRICS expanded its membership and institutional framework, creating its own development bank and reserve arrangements, and pursuing initiatives to challenge global dollar dominance by promoting multipolarity in finance, trade, and geopolitics.

From Dollar Dominance to a Multipolar Currency Order: Economic and Geopolitical Implications

Currently, the overwhelming reliance on the U.S. dollar exposes countries to vulnerabilities stemming from its monetary policy decisions or geopolitical developments. By promoting the use of multiple reserve currencies, countries can mitigate these risks, reducing their susceptibility to unilateral economic pressure. In addition, direct currency settlements between trading partners eliminate the need for dollar conversion, reducing costs for businesses and consumers while improving trade efficiency and economic cooperation. Using blockchain technology, BRICS Pay would ensure secure and decentralized transactions, enabling real-time interactions between countries. A digital service that allows the use of native BRICS currencies in cross-country operations. BRICS Pay would serve multiple purposes, including facilitating international trade, streamlining cross-border payments between companies, supporting investments, and fostering microfinance initiatives.

Sanctions effectiveness would diminish significantly if major economies could conduct trade and finance outside the dollar system. Countries facing geopolitical and geo-economic tensions with Washington would gain substantial policy flexibility. The greatest geopolitical risk lies in the potential for a “confrontational non-system” where dollar-aligned and non-dollar blocs/multipolar currency systems operate in opposition rather than cooperation. The monetary transition could accelerate the formation of new economic and political alliances while weakening existing relationships.

Petro-Dollar vs Petro-BRICS

The petrodollar system, established in the early 1970s, solidified the US dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency by dominating global oil trade in USD, creating consistent demand for US dollars and assets like treasury bonds, and integrating with international financial systems like SWIFT. In contrast, Petro BRICS represents efforts by the BRICS bloc, bolstered by the inclusion of major oil producers like Saudi Arabia and UAE, to shift energy trade away from the dollar toward national currencies or a potential common BRICS currency, aiming to escape US financial dominance, sanctions, and the “weaponization of finance.”

Russia and China already settle most energy trade outside the dollar, with India using rupees or dirhams for Russian oil purchases, while initiatives like BRICS Pay, digital currencies and bridge project for CBDCs), and new inter-BRICS clearing systems are being developed to bypass dollar-based infrastructure. The motivations include achieving economic autonomy, reducing vulnerability to US interest rates and financial crises, and supporting a multipolar global order. However, challenges persist, including the dollar’s unmatched global liquidity (60% of reserves), interoperability issues requiring dollars as an intermediary, technical and regulatory hurdles in creating alternative systems, and economic imbalances, such as India’s rupee surpluses in Russian banks.

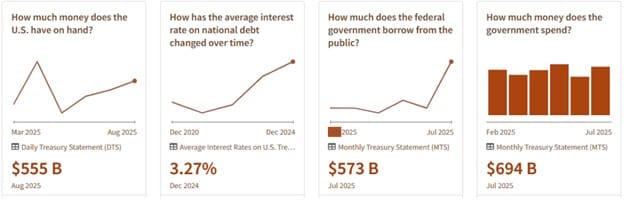

U.S. Fiscal Debt and the Potential Impact of a BRICS Currency

BRICS has been actively exploring ways to reduce reliance on the U.S. dollar in trade and investment. If such a currency were successfully adopted for intra-BRICS transactions, global demand for the dollar could gradually decline. Lower demand for dollars implies lower demand for U.S. Treasury bonds, which in turn would force Washington to raise interest rates in order to attract investors. Higher borrowing costs would mean larger interest payments, thereby accelerating the growth of the fiscal deficit. In such a scenario, American policymakers would face difficult choices: increasing taxes, reducing government spending, or engaging in even more borrowing, each of which carries political and economic risks. Yet, while this prospect sounds disruptive, it is important to recognize the resilience of the dollar’s role in global finance. The U.S. financial system benefits from a set of entrenched advantages, deep and liquid capital markets, reliable legal frameworks, and a long history of stability, that make dollar assets uniquely attractive. Additionally, the network effects of widespread dollar use create a self-reinforcing cycle, because everyone already uses the dollar, it remains the most convenient choice for trade, finance, and investment.

China has introduced the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) to facilitate international transactions in RMB. CIPS has expanded to include over 1500 participants globally, advancing the trend of moving away from the US-controlled SWIFT system. Additionally, China has launched its central bank digital currency in Guangdong, aimed at reducing transaction costs and enhancing cross-border efficiency, which is crucial for future BRICS trade.

India imports substantial goods from Russia but exports relatively little to Russia, creating a surplus of rupees that Russia may find difficult to utilize. A potential BRICS currency, possibly backed by a basket of currencies or commodities, could address this issue. India’s objective within BRICS is to establish a robust multilateral financial system that ensures economic stability and sovereignty for its members.

In conclusion, the rise of a BRICS currency could represent the beginning of a gradual diversification away from the dollar, but it is unlikely to overturn the system overnight. The United States’ fiscal debt will continue to grow as long as deficits persist, but its ability to finance this debt cheaply hinges on the dollar’s reserve status. Thus, while the BRICS initiative may not immediately dethrone the dollar, it introduces a new variable into the complex equation of America’s fiscal future and its position in the world economy.

Impact on BRICS trade

Ultimately, BRICS trade will evolve through a slow rebalancing of global financial flows rather than an immediate break with the U.S. dollar. The long term goal for BRICS is to create an independent economic ecosystem that’s powered by a new digital currency backed by tangible assets like gold and other select commodities. By drawing on their collective weight, they already represent 36.7% of global GDP in PPP terms and 45.2% of the world’s population.

BRICS+ countries seek to convert absolute scale into sustained geopolitical leverage. With their share of global merchandise exports expected to surpass that of the G7 by 2026, a unified currency stands as the pivotal instrument for realizing this transformation. Member economies would be less exposed to fluctuations in the U.S. dollar’s value and less affected by American interest rate decisions. This creates a more predictable trading environment. For members facing economic sanctions that restrict their access to the dollar-based financial system, the new currency provides an alternative channel to continue trading with other BRICS partners, effectively making such sanctions less potent.

In the short term, the impact of the introduction of a new currency seems modest. As several barriers still pertain such as the US dominance in global finance, accounting for the vast majority of forex and derivatives markets, supported by deep liquidity and trust in American institutions. Even so, BRICS is making clear its intent to gradually lessen reliance on the dollar. Member states have emphasized the importance of experimenting with alternative arrangements and reinforcing internal trade mechanisms to cushion against external shocks, including tariff pressures from the U.S. The process is best seen as a measured recalibration, one that strengthens resilience yet acknowledges the continued centrality of the dollar in international trade.

Global Trade Settlements and Forex Reserves

BRICS members are developing systems that enable trade settlements in local or gold-backed currencies, bypassing Western financial networks such as the SWIFT system. This shift encourages member nations to increase precious metal holdings and strengthens bilateral trade among these emerging economies. Consequently, intra-BRICS trade using non-dollar currencies is accelerating, though it remains relatively small compared to global trade flows.

As of 2025, the U.S. dollar’s share of global foreign exchange (FX) reserves is approximately 57%, down from about 72% in 2001. Also, about 54% of global exports are invoiced in dollars, and 88% of all foreign exchange transactions involve the dollar. Despite its dominance, BRICS initiatives are accelerating diversification in global trade. Notably, renminbi (RMB) settlements account for 50% of intra-BRICS transactions in 2025.

Implementation of BRICS currency or gold-backed trade systems promotes direct trade among BRICS members. While non-dollar settlements are expected to expand regionally, significant challenges remain before such systems can achieve broader global adoption.

Challenges for BRICS currency

An important risk in creating a single BRICS currency is the economic disparity among the BRICS nations’ economic structures, growth rates and degrees of development. China’s economy is characterized by a strong emphasis on industrialization and exports, whereas India’s economy is reliant on services and domestic consumption. Russia and Brazil are significant exporters of commodities, and have economies that are highly responsive to global price swings in oil and agricultural products, respectively. South Africa, with its distinctive socio-economic difficulties, introduces an additional level of complexity. The divergences in economic cycles among BRICS countries result in a lack of synchronisation, posing challenges in implementing a uniform monetary policy that caters to all members. BRICS lack a shared payment system and many members within BRICS face heavy sanctions (like Russia and Iran). This makes it difficult for a combined currency as the ill effects of these sanctions could flow into it too.

Harmonizing banking systems, creating a central bank, and aligned regulations are required. There is also the cost of printing new currency, upgrading infrastructure, and public education campaigns. Transition will be followed by short-term instability in inflation, unemployment, and exchange rates. Furthermore, the act of negotiating the political terrain and achieving consensus on important issues, such as exchange rate systems and governance structures, has the potential to impede or even disrupt the implementation process. Therefore, although the idea of a consolidated currency for the BRICS nations has advantages, the actual challenges and expenses involved emphasize the importance of preparation, collaboration and economic readiness.

BRICS’ Internal Test: Managing China’s Dominance

While the idea of a BRICS currency offers a chance to reduce the world’s reliance on the U.S. dollar, one of the major obstacles lies within the group itself, the concern that China could dominate the initiative.

China’s economy is the giant of the group. This economic gap automatically gives Beijing more leverage in shaping the rules of a potential BRICS currency. Smaller economies fear that their voices may be overshadowed, leaving them with little influence in critical decisions. Another fear is that a BRICS currency could be designed in a way that indirectly promotes the Chinese yuan. China has long sought to internationalize its currency, but progress has been slow. Through BRICS, the yuan could gain a new platform, turning the “common currency” into a disguised extension of Chinese monetary policy.

India and China have ongoing border disputes and strategic competition. This tension makes India cautious about joining a currency plan that might strengthen China’s economic reach. Other members, like Brazil and South Africa, also share concerns about putting too much power in one country’s hands.

In theory, a BRICS currency could be a powerful step toward reducing dependence on the U.S. dollar. But in practice, the elephant in the room is China’s overwhelming dominance. Unless the group finds a way to create a fair and transparent system of governance, this fear may continue to stall progress. For BRICS, the challenge is not just creating a new currency, it’s creating one that all members can trust.

Industry Specific Trajectories in De-dollarization

Industry specific de-dollarization could reshape global markets in ways that vary sharply across sectors. In the energy sector, the gradual use of other currencies for oil and gas trade could reduce U.S. sanctions leverage, alter pricing benchmarks, and shift reserve currency demand. In manufacturing and global supply chains, the transaction costs may become lower, but could also fragment trade settlements, requiring costly hedging infrastructure. For banking and finance, digital payment systems could weaken dollar-centric liquidity networks, pressuring banks to diversify reserves and payment rails, while also spurring innovation in cross-border settlement technologies. In commodities and metals, shifts away from dollar pricing may create multiple parallel benchmarks, raising volatility but also giving producer nations more influence. Finally, in technology and digital services, de-dollarization could accelerate the rise of alternative settlement platforms and central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), challenging the dominance of U.S. tech firms in financial infrastructure. Overall, sectoral de-dollarization may foster a more multipolar financial landscape, but with added complexity, higher short-term costs, and uneven benefits depending on industries’ exposure to U.S. trade, finance, and sanctions.

Economic Mechanisms and Implementation Pathways

A BRICS currency could likely be digital and used for trade and reserves. Its value could be pegged to a basket of BRICS currencies or commodities like gold to ensure stability and neutrality. A joint monetary authority would manage supply and policy. Implementation would start with government-level trade, supported by digital infrastructure, and expand gradually. Institutions like the New Development Bank could play a key role, but new bodies may be needed to manage monetary policy, enforce rules, and build trust.

Strong institutional infrastructure is essential for the currency’s credibility, stability, and long-term adoption. Furthermore, the digital infrastructure for a BRICS currency would form the technological backbone enabling secure, fast, and efficient cross-border transactions. This would likely include a blockchain-based payment system, digital wallets for central banks and large institutions, and interoperable platforms connecting national financial systems. The system would need to support real-time settlement, smart contract capabilities, and strong cybersecurity protocols to ensure trust and resilience. It would also require data centers, encryption standards, and possibly a permissioned distributed ledger shared across BRICS nations. This infrastructure is key to reducing reliance on Western systems like SWIFT and enabling de-dollarized trade.

Finally, the pathway to reserve competition may not be to replace the dollar, but to decentralize reserve holdings across a basket of currencies. BRICS could promote a multi-reserve world, where the dollar coexists with possibly a BRICS-backed digital currency or commodity-linked asset. This would reflect the shifting balance of global economic power without requiring the complete dethroning of the dollar and would thus build financial infrastructure, credibility, and trust across several dimensions.

Future Projections and Strategic Implications

The BRICS and its block already holds close to 45% of world population and contributes 35% to world GDP. However the ultimate implication of the world order is still unclear. Some analysts predict that BRICS+ could evolve to be a powerful anti western force and could complicate and deepen the divide between G20 and the UN. The prospect of a BRICS currency encapsulates a broader contest over the future of global financial governance. The BRICS bloc’s leaders have openly sought to reform the Western-led monetary order and reduce the U.S. dollar’s entrenched dominance.

BRICS-led currency envision a more multipolar system less vulnerable to dollar exchange fluctuations, pointing to steps like increased bilateral currency settlements. However, forging a unified BRICS currency faces formidable hurdles, the bloc lacks the deep financial integration, a common banking, fiscal, and macroeconomic framework, that such a project would demand, and skeptics note that the dollar still underpins over 80% of global trade, casting doubt on whether a new BRICS unit could be sufficiently stable or trusted to displace it.

In practice, BRICS initiatives have coalesced around gradual “de-dollarization” rather than an immediate currency union. These trends could over time chip away at the edges of U.S. dollar dominance, and some analysts warn that sustained de-dollarization efforts may eventually undermine the dollar’s strength and U.S. economic influence. Nevertheless, the most likely trajectory is one of incremental diversification rather than outright replacement. Given the dollar’s entrenched network advantages and the lack of comparably liquid alternatives on the world stage, it is widely expected to retain its central role in global trade, investment, and reserves for the foreseeable future.

References Used

-

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (n.d.). Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER). Retrieved September 2025, from https://data.imf.org/regular.

aspx?key=41175 - Federal Reserve. (n.d.). The Dollar. Retrieved September 2025, from https://www.

federalreservehistory.org/ essays/dollar - Bretton Woods Project. (n.d.). The Bretton Woods System. Retrieved September 2025, from https://www.

brettonwoodsproject.org/ - U.S. Department of the Treasury. (n.d.). Gold Standard and Fiscal Policy. Retrieved September 2025, from https://home.treasury.gov/

- Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). (n.d.). Dollar Dominance and De-Dollarization. Retrieved September 2025, from https://www.cfr.org/

backgrounder/dollar-dominance- and-de-dollarization - JPMorgan. (2025). De-dollarization: The end of dollar dominance? Retrieved September 10, 2025, from https://www.jpmorgan.com/

insights/global-research/ currencies/de-dollarization - Wikipedia. (2005). History of the United States dollar. Retrieved September 10, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

History_of_the_United_States_ dollar - Brookings Institution. (2022). The global dollar cycle. Retrieved September 10, 2025, from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-

content/uploads/2022/09/BPEA- FA22_WEB_Obstfeld-Zhou.pdf - Brookings Institution. (2016). The Dollar’s Role in the International Monetary System. Retrieved September 10, 2025, from https://www.brookings.edu/

events/the-dollars-role-in- the-international-monetary- system/ - Investopedia. (2020). Understanding Reserve Currency: The U.S. Dollar’s Global Role. Retrieved September 10, 2025, from https://www.investopedia.com/

terms/r/reservecurrency.asp - NordFX. (2024). History of the US Dollar: From Inception to Global Dominance. Retrieved September 10, 2025, from https://nordfx.com/en-IN/

useful-articles/916-US_dollar_ history - BRICS Council. (2025). The history of BRICS. Retrieved September 10, 2025, from https://bricscouncil.ru/en/

history - Carnegie Endowment. (2025). BRICS Expansion and the Future of World Order: Perspectives from Member States, Partners, and Aspirants. Retrieved September 10, 2025, from https://carnegieendowment.org/

research/2025/03/brics- expansion-and-the-future-of- world-order-perspectives-from- member-states-partners-and- aspirants - IMF. (2024). Dollar Dominance in the International Reserve System: An Update. Retrieved September 10, 2025, from https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/

Articles/2024/06/11/dollar- dominance-in-the- international-reserve-system- an-update - Britannica. (2025). BRICS. Retrieved September 10, 2025, from https://www.britannica.com/

topic/BRICS - Investopedia. (2025). BRICS. Retrieved September 10, 2025, from https://www.investopedia.com/

terms/b/brics.asp - Institute for Policy & Engagement – Sierra Leone (IPE-SL). (2023, August 17). The multipolar dollar. IPE-SL. https://ipe-sl.org/multipolar-

dollar/ - Institute of Geoeconomics. (2025, June 21). From dollar hegemony to currency multipolarity? Institute of Geoeconomics. https://

instituteofgeoeconomics.org/ en/research/2025062121/ instituteofgeoeconomics - Nacucchio, L. (2025, January). Global de-dollarization: Trends, challenges, and future impact. Payments CMI. https://paymentscmi.com/

insights/global-de- dollarization-us/paymentscmi - Prasad, E. (2020, May 21). The future of dollar hegemony. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/blog/

future-dollar-hegemony - Raghavan, P. (2023, March 25). The geopolitics of de-dollarisation. Deccan Herald. https://www.deccanherald.com/

opinion/the-geopolitics-of-de- dollarisation-3206898 - Subramanian, A., & Kessler, M. (2009, November). The renminbi bloc is here: Asia down, rest of the world to go? (Policy Research Working Paper No. 5147). World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.

org/curated/en/ 470961468041977091/pdf/ WPS5147.pdf - Monica, L., & Sekararum, P. (2025, August 16). India challenges dollar, invites BRICS countries to pay in rupees. IDNFinancials. https://www.idnfinancials.com/

news/56631/india-challenges- dollar-invites-brics- countries-to-pay-in-rupees (idnfinancials.com) - Gift, M. M. (2024, October 28). The BRICS currency conundrum: Weighing the pros and cons of a unified monetary system. Africa Policy Research Institute (APRI). https://afripoli.org/the-

brics-currency-conundrum- weighing-the-pros-and-cons-of- a-unified-monetary-system (blogs.griffith.edu.au) - Bank for International Settlements. (2024, June 30). Annual Economic Report 2024. https://www.bis.org/publ/

arpdf/ar2024e.pdf (Bank for International Settlements) - Boz, E., Casas, C., Georgiadis, G., Gopinath, G., Le Mezo, H., Mehl, A., & Nguyen, T. (2020, July 17). Patterns in invoicing currency in global trade (IMF Working Paper No. 2020/126). International Monetary Fund. https://doi.org/10.5089/

9781513550435.001 (IMF) - Weiss, C. (2025, September). De-dollarization? Diversification? Exploring central bank gold purchases and the dollar’s role in international reserves (International Finance Discussion Papers No. 1420). Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. https://doi.org/10.17016/IFDP.

2025.1420 (Federal Reserve) - Shalal, A. (2024, June 25). US dollar’s dominance secure, BRICS see no progress on de-dollarization—Report. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/

markets/currencies/us-dollars- dominance-secure-brics-see-no- progress-de-dollarization- report-2024-06-25/ (Reuters) - J.P. Morgan Global Research. (2025, July 1). De-dollarization: Is the US dollar losing its dominance? J.P. Morgan. https://www.jpmorgan.com/

insights/global-research/ currencies/de-dollarization (JPMorgan) - Choyleva, D. (2025, January 6). Petrodollar to digital yuan: China, the Gulf, and the 21st-century path to de-dollarization. Asia Society Policy Institute, Center for China Analysis. https://asiasociety.org/sites/

default/files/2025-01/Enodo- Petrodollars%20to%20Digital% 20Yuan.pdf (Asia Society) - Boocker, S., & Wessel, D. (2024, August 23). The changing role of the US dollar. Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/

articles/the-changing-role-of- the-us-dollar/ (Brookings) - Garcia, C. (2025, September 4). Why the world’s bankers are ghosting Treasurys for gold—and what it means for your 401(k). MarketWatch. https://www.marketwatch.com/

story/why-central-banks-are- ghosting-treasurys-for-gold- and-what-it-means-for-your- 401-k-eec0cbb9 (MarketWatch) - Patrick, S., Hogan, E., Stuenkel, O., Gabuev, A., Tellis, A. J., Zhao, T., de Carvalho, G., Gruzd, S., Hamzawy, A., Kebret, E., Noor, E., Sadjadpour, K., Al-Ketbi, E., Mijares, V., Eguegu, O., Sager, A., Yabi, G., Ülgen, S., & Nguyen, T. (2025, March 31). BRICS expansion and the future of world order: Perspectives from member states, partners, and aspirants. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/

research/2025/03/brics- expansion-and-the-future-of- world-order-perspectives-from- member-states-partners-and- aspirants?lang=en (Carnegie Endowment) - Bai, G. (2024). From de-risking to de-dollarisation: The BRICS currency and the future of the international financial order. Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. https://thetricontinental.org/

wenhua-zongheng-2024-1- derisking-dedollarisation- brics-currency/ (Tricontinental Institute) - BRICS and the dollar dilemma: New global currency blocs likely to form to counter greenback. (2023, August 25). Daily Maverick. https://www.dailymaverick.co.

za/article/2023-08-25-brics- and-the-dollar-dilemma-new- global-currency-blocs-likely- to-form-to-counter-greenback/ (dailymaverick.co.za) - Srivastava, D. K. (2024, October 30). BRICS+ to pave the way for a multipolar currency era. EY India. https://www.ey.com/en_in/

insights/tax/economy-watch/ brics-to-pave-the-way-for-a- multipolar-currency-era (EY) - International Monetary Fund. (n.d.). Currency composition of official foreign exchange reserves (COFER) [Data set]. IMF Data. Retrieved September 13, 2025, from https://data.imf.org/en/

datasets/IMF.STA:COFER (data.imf.org)

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (n.d.). Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER). Retrieved September 2025, from https://data.imf.org/regular.